Archive for the ‘human-rights’ Category

random thoughts on human rights

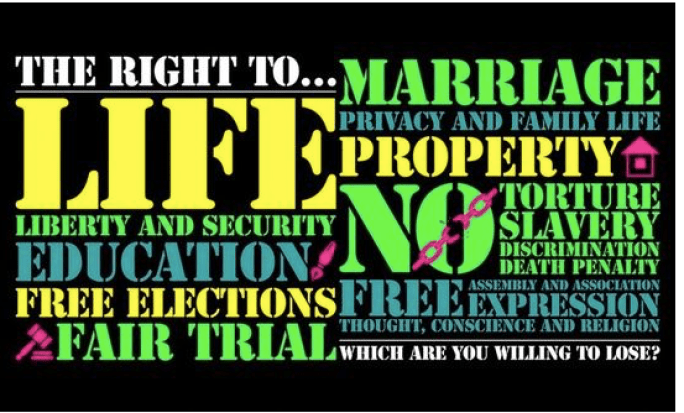

Over the years I’ve had arguments and discussions with people, and semi-disputes online, about the status of human rights, and rights in general. Some have been quite dismissive of their ‘mythical’ nature, others like Scott Attran have described them as a crazy, transcendental idea invented by a handful of Enlightenment figures back in the day, and boosted by the reaction to world wars in the 20th century. There have been objections by certain states claiming they don’t give sufficient cognisance to ‘Asian values’, and Moslem countries have argued that they need to be amended in accordance with Shar’ia Law.

The first point I would make is that, granted that rights are a human invention, that doesn’t make them ‘unreal’ or in some sense nugatory. Tables, chairs, buildings, computers, bombs, democracy and totalitarianism are all human inventions, but very real, if not all of equal value. To describe human rights as a form of transcendentalism also doesn’t make sense to me. Certainly if you say ‘God has granted certain inalienable rights…’ you’re using transcendental language, but that language is, I think, superfluous to the idea of rights, which, I would argue, is grounded in both empiricism and pragmatism.

I would also argue, no doubt more controversially, that human rights make little sense if based entirely on the individual. They are principally about human relations, and so imply that each individual is part of a larger social entity, within which they may be accorded ‘freedoms from’ and ‘freedoms to’. Aristotle puts the point well in his Politics:

the individual, when isolated, is not self-sufficing; and therefore he is like a part in relation to the whole. But he who is unable to live in society, or who has no need because he is sufficient for himself, must be either a beast or a god: he is no part of a state.

It follows that rights must be under the guardianship of states and enshrined in and upheld by their laws. This is vital because individuals often have competing interests, and it’s sometimes the case that particular individuals don’t recognise or understand that there’s a common, social interest beyond their own. This is the difficulty with rights – because we often think of them as my rights or my freedoms, we fail to understand that these rights, though granted in some sense to individuals, must be based on the thriving of the wider social sector, whether we’re referring to village, tribe or state. And it is to these larger social entities – states, or civilisations – that we owe our phenomenal success as a species, for better or worse.

This raises a question of whether the best human rights should flow from the best states, or vice versa. Interestingly, Aristotle and his students collected some 150 constitutions from the world of Greek poleis or city-states in order to devise the best, most ‘thriving’ city-state possible, which of course should have involved comparing the constitutions with the situation on the ground in those city-states. We don’t know if any such comparison was made (it’s very doubtful), but it does suggest that Aristotle thought that the state, via its constitution, was the engine of a thriving citizenry rather than the other way around.

Turning to rights in the modern world, the unfortunate claim by Tom Paine in his Rights of man (1791) that ‘rights are inherently in all the inhabitants’ of a state, has helped to create the confusion about rights being ‘natural’ to humans, like having two legs and a complex prefrontal cortex (the latter being largely the result of living in increasingly complex and organised society). If we’re to take human rights seriously, we need to be honest about their a posteriori nature. They need to be seen as the result of our understanding of how to create an environment that best suits us, as the most socially constructed mammals on the planet. In that respect, we’ve come a long way, not only from Aristotle (who excluded women and slaves from his citizenry), but also from the the late eighteenth century revolutionaries (who executed Olympe de Gouges for daring to even suggest adding women to the rights-owning citizenry of her own nation). Indeed, examining the issue of rights historically should remind us that they need to be updated on the basis of our ongoing advances in knowledge. The 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, by this understanding, should certainly not be fixed in stone.

My views, of course clash with ‘natural law’ notions of human rights, which tend to be based on the individual an sich, and have claims to be outside of social or temporal considerations.

If we try to think of rights as ‘natural’ or self-evident, rather than something we construct to help us understand what we owe to, and might expect from, the best of civil states, we might well agree with Alasdair McIntyre’s view that there’s nothing natural or self-evident, say, about allowing people, by right, the freedom to express or live by their religious views. Many religious views are notoriously idiosyncratic and sometimes offensive from an outsider’s perspective, and adding the ‘no harm’ principle doesn’t suffice to smooth things over. The jury is very much out as to whether religion is, or has been, a benefit to society, but it’s well known that some religions have, in the past, engaged in human sacrifices. And even today new religions might crop up which may involve practices that the majority would find inimical both to individual and social well-being. And of course the very definition of religion is far from being self-evident. Article 18 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, states:

Everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion; this right includes freedom to change his religion or belief, and freedom, either alone or in community with others and in public or private, to manifest his religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship and observance.

However, it makes no attempt to define religion, and in the same Article it claims the right of all to ‘manifest his… belief…in practice and observance’. This, if taken literally, is absurd, as a person might hold a belief that slave-owning is okay, and is given the green light by this Article to ‘manifest that belief in practice.. and observance’. No doubt my criticism doesn’t capture the liberal ‘spirit’ of the Article, but it does highlight an obvious problem. People do act on beliefs, and many actions, based on those beliefs, can be harmful, and subject to criminal prosecution. The law, of course, prosecutes acts, not thoughts, so we know that we’re free to think what we want – we don’t need a ‘right’ to protect this. I won’t try to define religion, but at least it seems to involve both beliefs and actions. Actions will be subject to civil and criminal law, so it might be argued that rights don’t find a place there. Beliefs are private unless and until they’re acted on, in which case they’ll be subject to law. So there’s a question whether rights have a place there also.

The more I look at human rights, the more difficulties I see. Let me take, more or less at random, Article 21 of the UDHR:

(1) Everyone has the right to take part in the government of his country, directly or through freely chosen representatives.

(2) Everyone has the right of equal access to public service in his country.

(3) The will of the people shall be the basis of the authority of government; this will shall be expressed in periodic and genuine elections which shall be by universal and equal suffrage and shall be held by secret vote or by equivalent free voting procedures.

Section 3 here reads like a directive, but I agree that every member of a state should be allowed at least the opportunity to cast a vote for government. In Australia, voting is compulsory for eligible parties, as it is in some 22 countries (though enforced in only 11). It’s questionable whether compulsion accords with human rights and freedoms, but given the socially constructed nature of humanity, voting should definitely be encouraged as a duty, at the very least. The ideal, of course, would be that everybody is aware of what they owe to the state, and their interest in creating and maintaining a state that is beneficial to the whole and so to themselves as a part.

There is no doubt in my mind that participatory democracies make for better states than any alternatives, and if this can be bolstered by human rights language that is fine, though I think that interest and duty (what we owe to ourselves and others) makes more sense as an argument. The ‘Asian values’ objection here (revisited recently by the Chinese oligarchy) is bogus and self-serving, as evidenced by the success of democratic nations such as Japan, South Korea and Taiwan. There is a tendency in Asian nations to be more collectivist in thinking and behaviour than in many European nations, and especially the USA, but this would make them more attracted to participatory democracy, not less.

Concluding remarks – the more I look at rights, the more questionable I find them. I would rather encourage a neo-Aristotelian way of thinking. We’re now political animals more than ever, in a wider sense than Aristotle saw it, because civilisation itself is political, and civilisation is hardly something we can opt out of. I don’t advocate world government – that was an impossible if admirable ideal – but I certainly advocate intergovernmental co-operation as opposed to zero sum nationalism. We need to make an all-out effort to improve our state structures and understanding between them for the sake of all their members (and the rest of the biosphere).