Archive for the ‘war’ Category

a year after Pudding’s invasion

Canto: So more than a year has passed since Mr Pudding sent Russian forces into Ukraine, giving no good reason, to the world or to those he believes to be his subjects…

Jacinta: Well, for domestic consumption he insisted that it was a special operation – though whether it was to denazify the place or to simply incorporate it into the Fatherland, I’m not Russian enough to know. I suspect he doesn’t feel it overly necessary to explain exactly why he’s sending a proportion of the Russian population into harm’s way. He loves his country and he’ll never do it no wrong.

Canto: We’ve been listening, or half listening, to a number of well-reputed pundits on the situation, including Julia Ioffe, Fiona Hill, Timothy Snyder, Vlad Vexler, Marie Yovanovich and Bill Taylor – most of them United Staters, but with independent minds and humanist principles….

Jacinta: Haha, careful what you’re saying. We also watched recently a series of interviews with a cross-section of ‘ordinary Russians’ both for and against the war and their everlasting leader. And really it’s the same everywhere, no matter the country or type of government. So many just say ‘I’m not a political person,’ and make vague but dogmatic remarks about patriotism and fully backing the smarts at the top.

Canto: The impression I got from those interviews was that the war wasn’t much affecting them personally, and I suppose that as long as that’s the case, complacency will rule.

Jacinta: Well it’s not easy to ascertain the death toll, for Russians, of this operation. The New York Times, in an article from early February, claimed around 200,000 Russian deaths, but it was pretty vague as to sources. To be fair, they’re dealing with a country notorious for disinformation:

… officials caution that casualties are notoriously difficult to estimate, particularly because Moscow is believed to routinely undercount its war dead and injured…

Canto: Both sides would be keen to keep a lid on numbers for reasons of morale, but this has surely been the worst conflict we’ve seen in our lifetimes, in terms of loss of life…

Jacinta: Ahem..

In 1995 Vietnam released its official estimate of the number of people killed during the Vietnam War: as many as 2,000,000 civilians on both sides and some 1,100,000 North Vietnamese and Viet Cong fighters.

That’s according to Encyclopaedia Britannica. But of course we have no idea when this current war will end or what the actual death toll numbers are today.

Canto: So what will bring it to an end? Most commentators on the NATO side are saying we need to do everything in our power to help Ukraine win as quickly and decisively as possible. That doing only enough to prevent Ukraine from losing would be a disastrous approach, with more lives lost. That would seem to mean the most sophisticated and destructive weapons, sent by NATO countries, since no NATO countries are prepared to supply soldiers, and in terms of manpower, Mr Pudding has the edge, since he’s at present prepared to sacrifice everyone he can muster to the cause, and that’s a lot more cannon-fodder than Ukraine has.

Jacinta: Yes, and I’m hearing mixed views, and noting some foot-dragging on the sending of materiel…

Canto: Well with the winter just ending, they’re talking of spring offensives, so these next months might be decisive. I’ve heard that the Chinese Testosterone Party, in the form of Chairman Xi, has let it be known that the nuclear option must definitely be ruled out. That’s important – according to one expert who strikes me as reliable, China is very much the senior partner in its relation with Russia, obviously for economic reasons, though that would stick in the Pudding’s craw…

Jacinta: Yuk. Yes, I’ve long considered that going nuclear would be the Pudding’s only real chance for victory, only it wouldn’t… There’d be retaliation, and no winners… It just has to be a non-option.

Canto: But I can’t see him giving up at this stage. There has just been a decision, on the first anniversary of this war, to send Leopard tanks to msUkraine, something Zelensky has long been asking for. They’re also hoping for fighter jets, but none are currently forthcoming. It seems to have been a bit like pulling teeth, though according to a BBC article I’m reading, one reason for the delay is the need to train Ukrainian forces in the operation of this sophisticated weaponry. The BBC also has an interesting graphic on the amount of money spent per nation (including the EU) on military aid to Ukraine. The USA has spent almost three times more than all the European nations put together.

Jacinta: Which is a bit surprising, but then the USA has long been obsessed with being a military behemoth, and the toughest kid in town.

Canto: Well, if you can’t be the smartest… Germany is now sending Leopard 2 tanks as well. The BBC article is long on detail of the materiel being supplied, about which of course we’re far from expert, but here’s a list: as to tanks, there’s the Leopard 2, the Challenger 2, the T-72M1, and the M1 Abrams. As to combat vehicles, the Stryker armoured fighting vehicle and the Bradley fighting vehicle. For air defence, the Patriot missile system, the S-300 air defence system and Starstreak missiles. Other nasties include the Himars rocket launcher system, M777 howitzers, anti-tank weapons and drones.

Jacinta: Yes it all sounds impressive – but as to jets, it’s not just the lack of training – many are worried that this might take the war inside Putinland, though I don’t personally see a big problem with that.

Canto: True, Mr Pudding would hardly be in a position to complain, but the general argument might be that innocent people would be being killed on both sides. It’s difficult, as Pudding seems unfazed by the numbers he’s committing to this operation…. But I don’t think any restrictions should be placed on how they use the materiel supplied to them. They’re fighting for their existence, and hitting at the heart of Russia might be the best way to get Pudding to stop.

Jacinta: But mightn’t it widen the conflict? China could get involved, say…

Canto: I don’t think so. We – those of us supporting Ukraine – would need to keep dialogue going with China and other countries with ties to Russia. Not that they don’t know who’s to blame for this war.

Jacinta: Okay so let’s look at the current situation. More weapons are being sent to Ukraine, but currently there’s a big battle around Bakhmut, in the Donetsk region of eastern Ukraine. Russian forces are trying to encircle the city, which has been the site of some of the most intense fighting in the war. It has probably suffered more damage than any other Ukrainian city, and has changed hands a couple of times. Ukrainians are just holding onto it for the time being, and it’s likely to change hands a few times more before the end.

Canto: Yes, it’s the city centre they’re currently trying to capture, so that they can cut off supply lines from the west, so it seems. They already have control of the eastern suburbs. And I should say thank you to the various sources reporting on the action, whose accents I’m trying to get used to!

Jacinta: Yes, it’s like trying to be part of the action, like watching your favourite sports team trying to win, though the stakes are a million times higher, and the moral dimensions incalculably more significant.

Canto: Times Radio, from Britain, has been a good source of news and analysis on the war, and I’ve just watched one of their YouTube videos in which reporter Jerome Starkey talks about ‘Russia’s Wagner Group mercenaries’ being used as cannon fodder in the assault on Bakhmut, threatened with being shot if they retreat – which is both horrific and confusing. I thought mercenaries were volunteers by definition…

Jacinta: Well I think they’re more like professional soldiers for hire. But I can’t imagine anyone signing up for a paid job under those conditions. You could say they’ve been trapped by their own mercenary motives, though that hardly exonerates Pudding and his cronies….

Canto: There’s a Wikipedia article on the Wagner Group, for which the TLDR acronym might’ve been invented, but basically it’s a force of amoral military thugs under the pay of Pudding, and operating outside of any legal jurisdiction. As you can imagine, many of them are driven by far-right ideologies as well as macho ideation.

Jacinta: And to compensate for their teeny-weeny penises.

Canto: They’ve been around for about a decade, and of course have been associated with multiple war crimes and atrocities wherever Pudding’s whims have sent them. So getting back to Bakhmut, many of the Russians fighting there, whether part of the Wagner group or not, have been ‘recruited’ from prisons and press-ganged into service. They may have the numbers to take Bakhmut for the time being, but my uneducated guess is that NATO-Ukrainian weaponry and the ability to deploy that weaponry effectively will win out in the end.

Jacinta: Experts, if there are any for this scenario, are saying that there’s no sign of an end in sight. That it’ll drag on at least for the rest of this year.

Canto: Well it looks like Bakhmut will be retaken by the Russians for the time being, and hopefully the remaining residents can be evacuated before then, but it may be a Pyrrhic victory because sadly the place has already been reduced to near-rubble. Meanwhile money, arms and ammunition continue to be funnelled to the Ukrainians, China has been warned by the EU not to support Pudding with weapons, threatening ‘sanctions’, and the Cold War world continues to freeze over….

References

https://www.britannica.com/question/How-many-people-died-in-the-Vietnam-War

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wagner_Group

https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/3/4/russia-ukraine-war-list-of-key-events-day-374

A bonobo world, etc, 18: gender and aggression in life and sport

bonobos play-fighting

human apes play-fighting?

If anyone, like me, says or thinks that they’d like to be a bonobo, it’s to be presumed they don’t mean they’d like to live in trees, be covered in hair, have a shortened life-span, a brain reduced to a third of its current size, and to never concern themselves with why the sky is blue, how the Earth spins, and whether the universe is finite or infinite. What we’re really interested in is how they deal with particular matters that have bedevilled human societies in their infinite variety – namely sex, violence, effective community and the role of women, vis-a-vis these matters.

While making a broad generalisation about human society, in all its billions, might leave me open to ridicule, we seem to have followed the chimpanzee and gorilla path of male domination, infighting as regards pecking order, and group v group aggression, rising to warfare and nuclear carnage as human apes became more populous and technologically sophisticated. One interesting question is this: had we followed the bonobo path of female group bonding and controlling the larger males by means of those bonds, and of group raising of children causing reduced jealousies and infanticides, would we have reached the heights of civilisation, if that’s the word, and world domination that we have reached today?

I realise this is an impossible question to answer, and yet… Human apes, especially in post-religious societies, are recognising the power and abilities of their women more and more. Social evolution has speeded up this process, bringing about changes in single lifetimes. In 1793 Olympe de Gouges, playwright, abolitionist, political activist and author of the Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen, was guillotined by Robespierre’s disastrous Montagnard faction, as much for being a moderate as for being a woman. Clearly a progressivist, de Gouges opposed the execution of Louis XVI, and capital punishment generally, and favoured a constitutional monarchy, a system which still operates more or less effectively in a number of European nations (it seems better than the US system, though I’m no monarchist). Today, capital punishment generally thrives only in the most brutally governed nations, such as China, Iran and Saudi Arabia, though there are unfortunate outliers such as Japan, Singapore and arguably the USA (none of those last three countries have ever had female leaders – just saying). One hundred years after de Gouges died for promoting female equality and moderation, women were still being denied a university education in every country in the world. However in the last hundred years, and especially in the last fifty, we’ve seen dramatic changes, both in the educational and scientific fields, and in political leadership. The labours of to the Harvard computers, Williamina Fleming, Annie Jump Cannon, Antonia Maury and many others, working for a fraction of male pay, opened up the field of photometric astronomy and proved beyond doubt that women were a valuable and largely untapped intellectual resource. Marie Curie became the most famous female scientist of her day, and inspired women around the world to enter the scientific fray. Today, women such as Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier, of CRISPR-Cas9 fame, and Michelle Simmons, Australia’s quantum computing wizard, are becoming more and more commonplace in their uncommon intellect and skills. And in the political arena, we’ve had female leaders in Australia, New Zealand, the UK, Germany, Norway, Finland, Iceland, Denmark, Belgium, France, Portugal, Austria, Slovakia, Bulgaria, Romania, Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia, Serbia, Croatia, Russia (okay, in the eighteenth century), China (nineteenth century), South Korea, Myanmar, Pakistan, India, Indonesia, the Phillippines, Sri Lanka (the world’s first female PM), Israel, Ethiopia and Liberia, and I may have missed some. This may seem an incredible transformation, but many of these women were brief or stop-gap leaders, and were all massively outnumbered by their male counterparts and generally had to deal with male advisers and business and military heavyweights.

So it’s a matter of rapid change but never rapid enough for our abysmally short life spans. But then, taking a leaf from the bonobo tree, we should look at the power of female co-operation, not just individual achievement. Think of the suffragist movement of the early 1900s (the term suffragette was coined by a Daily Mail male to belittle the movement’s filletes), which, like the Coalition of Women for Peace (in Israel/Palestine) a century later, was a grassroots movement. They couldn’t be otherwise, as women were then, and to a large extent still are, shut out of the political process. They’re forced into other channels to effect change, which helps explain why approximately 70% of NGO positions are held by women, though the top positions are still dominated by men.

When I think of teams, and women, and success, two more or less completely unrelated fields come to mind – science and sport. In both fields cooperation and collaboration are essential to success, and more or less friendly competition against others in the field is essential to improve quality. Womens’ team sport is as competitive as that of men but without quite the same bullish, or chimp, aggressiveness, it seems to me, and the research backs this up. Sport, clearly, is a constructed form of play, in which the stakes are sometimes very high in terms of trophies, reputations and bragging rights, but in which the aggression is generally brought to an end by the final whistle. However, those high stakes sometimes result in foul play and overly aggressive attempts to win at all costs – and the same thing can happen in science. Sporting aggression, though, is easier to assess because it’s more physical, and more publicly displayed (and more likely to be caught on camera). To take my favourite sport, soccer, the whole object for each team is to fight to get and maintain possession of the ball for the purpose of scoring goals. This battle mostly involves finesse and teamwork, but when the ball is in open play it often involves a lot of positional jostling and other forms of physicality. Personally, I’ve witnessed many an altercation in the male game, when one player gets pissed off with another’s shirt-tugging and bumping, and confronts him chest-to-chest, nature documentary-style. The female players, when faced with this and other foul play, invariably turn to the referee with a word or a gesture. Why might this be?

In 1914, the American psychologist E L Thorndike wrote:

The most striking differences in instinctive equipment consists in the strength of the fighting instinct in the male and of the nursing instinct in the female…. The out-and-out physical fighting for the sake of combat is pre-eminently a male instinct, and the resentment at mastery, the zeal to surpass, and the general joy at activity in mental as well as physical matters seem to be closely correlated with it.

a bonobo world and other impossibilities 15

returning to the ‘farm’ in 1919 – 10 million dead, 21 million more mutilated

stuff on aggression and warfare

Warfare has long been a feature of human culture; impossible to say how far back it goes. Of course war requires some unspecified minimum number of participants, otherwise it’s just a fight, and one thing we can be certain of is that there were wars worthy of the name before the first, disputed, war we know of, when the pharoah Menes conquered northern Egypt from the south over 5000 years ago. The city of Jericho, which lays claim to being the oldest, was surrounded by defensive walls some three metres thick, dating back more than 9000 years, and evidence of weapons of war, and of skeletal remains showing clear signs of violent death by such weapons, dates back to 12000 years ago. None of this should surprise us, but our knowledge of early Homo sapiens is minuscule. The earliest skeletal data so far found takes us back nearly 200,000 years to the region now covered by Ethiopia in east Africa. We know next to nothing of the lifestyle and culture of these early humans. There’s plenty of dispute and uncertainty about the evolution of language, for example, which is surely essential to the planning of organised warfare. The most accepted estimates lie in a range from 160,000 to 80,000 years ago, but if it can ever be proven that our cousins the Neanderthals had language, this could take its origins back another hundred thousand years or more. Neanderthals share with us the FOXP2 gene, which plays a role in control of facial muscles which we use in speech, but this gene is regulated differently in humans.

In any case, warfare requires not only language and planning but sufficient numbers to carry out the plan. So just how many humans were roving about the African continent some 100,000 years ago?

The evidence suggests that the numbers were gradually rising, such that the first migrations out of Africa took place around this time, as our ancestors sought out fresh resources and more benign environments. They could also be escaping human enemies, or seeking out undisputed territory.

Of course there may have been as much collaboration as competition. We just don’t know. What I’m trying to get at is, were we always heading in the chimp direction of male dominance and aggression, or were there some bonobo traits that tempered this aggression? Of course, I’m not talking about influence – we haven’t been influenced, in our development, by these cousins of ours in any way. We only came to recognise them as cousins very recently. And with this recognition, it might be worth learning more from family.

Human warfare has largely been about the expansion or defense of territory, and it was a constant in Europe from the days of the Roman Empire until well into the nineteenth century. In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, armaments became far more deadly, and the 1914-18 war changed, hopefully for good, our attitude to this activity, which had previously been seen as a lifetime career and a proof of manliness. This was the first war captured by photography and newsreels, and covered to a substantial degree by journalism. If the Thirty Years’ War had been covered by photojournalists and national newspapers it’s unlikely the 1914-18 disaster would have occurred, but the past is another country. Territory has become more fixed, and warfare more costly in recent times. Global trade has become fashionable, and international, transnational and intergovernmental organisations are monitoring climate change, human rights, health threats and global economic development. Violent crime has been greatly reduced in wealthy countries, and is noticeably much greater in the poorer sectors of those countries. Government definitely pays a role in providing a safety net for the disadvantaged, and in encouraging a sense of possibility through education and effective healthcare. It’s noteworthy that the least crime-ridden countries, such as Iceland, New Zealand, Portugal and Denmark, have relatively small populations, rate highly in terms of health, work-life balance and education, and have experienced long periods of stable government.

Of course the worry about the future of warfare is its impersonality. This has already begun of course, and the horrific double-whammy of Horishima-Nagasaki was one of the first past steps towards that future. Japan’s military and ruling class had been on a fantastical master-race slaughter spree for some five decades before the bombs were dropped, but even so the stories of suffering and dying schoolchildren and other innocents in the aftermath of that attack make us all feel ashamed. And then what about Dresden? And Auschwitz? And Nanjing? And it continues, and is most egregious when one party, the perpetrator, has far more power than the other, the victim. Operation Menu, a massive carpet bombing campaign of eastern Cambodia conducted by the US Strategic Air Command in 1969 and 1970, was an escalation of activities first begun during the Johnson administration in 1965, in the hope of winning or at least gaining ground in the Vietnam war. There were all sorts of strategic reasons given for this strategy, of course, but little consideration was given to the villagers and farmers and their families, who just happened to be in the way. Much more recently the Obama administration developed a ‘kill list’, under the name Disposition Matrix, which has since been described as ‘potentially indefinite’ in terms of its ongoing targets. This involved the use of drone strikes, effectively eliminating the possibility of US casualties. Unsurprisingly, details of these strikes have been hard to uncover, but Wikipedia, as always, helps us get to the truth:

… Ben Emmerson, special investigator for the United Nations Human Rights Council, stated that U.S. drone strikes may have violated international humanitarian law. The Intercept reported, “Between January 2012 and February 2013, U.S. special operations airstrikes [in northeastern Afghanistan] killed more than 200 people. Of those, only 35 were the intended targets. During one five-month period of the operation, according to the documents, nearly 90 percent of the people killed in airstrikes were not the intended targets.”

Cambodians, Afghans, distant peoples, not like us. And of course it’s important to keep America safe. And the world too. That’s why the USA must never become a party to the International Criminal Court. The country is always prepared to justify its violent actions, to itself. And it’s a nation that knows a thing or two about violence. According to the Institute for Economics and Peace (IEP), the USA is ranked 121st among the most peaceful countries in the world.

References

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Drone_strike#United_States_drone_strikes

https://www.gfmag.com/global-data/non-economic-data/most-peaceful-countries

a bonobo world? 11

another bitter-sweet reflection on capacities and failures

I was in a half-asleep state, and I don’t know how to describe it neurologically, but subjectively I was hearing or being subjected to a din in my head, a kind of babble, like in an echoing school canteen. Then I heard a knocking sound above the din, then in a transforming whoosh all the din stopped in my head, it became silent apart from the knocking, and then, as a kind of wakening crystallisation clarified things, another sound, of trickling water. I quickly realised this was the sound from the shower above me, and the knocking was of the pipes being affected by the rush of hot water. But what really interested me was what had just happened in my brain. The din, of thought, or inchoate thought, or of confusedly buzzing neural connections, was dampened down instantly when this new sound forced itself into my – consciousness? – at least into a place or a mini-network which commanded attention. It, the din, disappeared as if a door had been slammed on it.

I can’t describe what happened in my brain better than this, though I’m sure that this concentration of focus, or activity, in one area of my brain, and the concomitant dropping of all other foci or activity, to facilitate that concentration, was something essential to human, and of course other animal, neurology. Something observed but not controlled by ‘me’. Something evolved. I like the way this is shared by mice and men, women and wombats.

But of course there are big differences too. I’ve described the experience, whatever it is, in such a way that a neurologist, on reading or listening to me, would be able to explain my experience more fully, or, less likely, be inspired to examine it or experiment with its no-doubt miriad causal pathways. I suppose this experience, though more or less everyday and unthreatening, is associated with flight-or-fight. The oddity of the sound, its difference from the background din, or perhaps rather my awareness of its oddity, caused a kind of brain-flip, as all its forces, or most of them, became devoted to identifying it. Which caused me to awaken, to marshall a fuller consciousness. How essential this is, in a world of predators and home intruders, and how much fun it is, and how useful it is, to try for a fuller knowledge of what’s going on. And so we go, adding to our understanding, developing tools for further investigation, finding those tools might just have other uses in expanding other areas of our knowledge, and the world of our ape cousins is left further and further behind. For me, this is a matter of pride, and a worry. I’m torn. The fact that I think the way I do has to do with my reading and my reflections, the habits of a lifetime. Some have nerdiness, if that’s what it is, thrust upon them. I’m fascinated by the human adventure, in its beginnings and its future. Its beginnings are connected to other apes, to old world and new world monkeys, to tarsiers, to tree shrews and rodents and so on, all the way back to archaea and perhaps other forms yet to be discovered. We need to fully recognise this connectivity. Its future, what with our increasing dominance over other species and the earthly landscape, our obsession with growth, our throwaway mindset, but also our ingenious solutions, our capacity for compassion and for global cooperation, that future is and always will be a mystery, just outside of our manipulating grasp, with every new solution creating more problems requiring more solutions.

A few hundred years ago, indeed right up to the so-called Great War of 1914, human warfare was a much-celebrated way of life. And we still suffer a kind of hero-worship of military adventurism, and tell lies about it. In the USA, many times over the most powerful military nation on earth, the media are always extolling the sacrifice of those who fought to ‘keep America safe’. This is a hackneyed platitude, considering that, notwithstanding the highly anomalous September 11 2001 attack, the country has never had to defend its borders in any war. Military casualties are almost certain to occur in a foreign country, where the USA is seeking to preserve or promote its own interest, generally against the interests of that country. In this respect, the USA, it should be said, is no better or worse than any other powerful country throughout history. The myth of military might entailing moral superiority, which began with the dawn of civilisations, dies hard, as ‘American exceptionalism’ shows.

But globalism, international trade, travel, communication and co-operation, is making for a safer and less combative human society than ever before. So, as militarism as a way of life recedes, we need to focus on the problems of globalism and economic growth. As many have pointed out, the pursuit of growth and richesse is producing many victims, many ‘left-behind’. It’s dividing families and creating a culture of envy, resentment and often unmitigated hatred of the supposedly threatening ‘other’. The world of the bonobo – that tiny community of a few tens of thousands – tinier than any human nation – a gentle, fun-loving, struggling, sharing world – seems as distant to us as the world of the International Space Station, way out there. And yet…

Operation Pressure Pump, the struggle with anti-Americanism, and the future of humanism (!?)

Having succumbed to the strange lure of Korean period dramas, and the not-so-strange allure of the incomparable Ha ji Won, in recent times, I’ve been reading a real history of Korea, Michael Seth’s fast-moving, highly readable book in the Brief History series.

Seth’s book moves perhaps a bit too quickly through the vast time-span of Korean civilisation before the twentieth century, but no matter, I was keen to find out more about the Korean War, its causes and consequences, about which I knew practically nothing.

In brief, the Korean War was an outcome of the Japanese occupation of the peninsula, and its surrender and withdrawal in 1945. The vacuum thus left was occupied by the Americans in the south, and the Russians in the north, a division demarcated arbitrarily by the 38th parallel. This quasi-official division, which seemed to go on indefinitely and which the Koreans were never consulted about, came as a massive affront to a people who had effectively governed their own undivided region for centuries.

Nevertheless, communism was in the air, and held a certain appeal for some of the Korean peasantry and some intellectuals, fed by Russian and Chinese propaganda. In the poorer north, Russian and local communist leaders were able to introduce reforms which had a direct and immediate benefit for the landless peasantry, while the Americans, apparently clueless about Korean politics and history, tried to maintain order by continuing some of the hated repressive measures of the Japanese.

People on both sides of the 38th parallel wanted and expected reunification of the country in the near future, which makes what eventually happened one of the great tragedies of the twentieth century. The north, under the discipline of Russian Stalinist policies of ‘x-year plans’ and ultra-nationalist workaholism, took the initiative, building up a powerful military force with which to invade the south and enforce reunification, and a Stalinist paradise. By this time Kim Il Sung had imposed himself as the Great Leader of the north, dealing ruthlessly with all rivals.

The north’s attack took the south completely by surprise, and was almost a complete success. They captured all the southern territory except for a small area around Busan, Korea’s second city in the south-east corner. By this time General MacArthur had been appointed to head the southern defence, and with American arms and reinforcements arriving quickly, the invaders were pushed back.

The northern invasion was extremely unpopular in the south, and few of the peasantry, who were generally better off than their northern counterparts, were interested in what Kim’s Stalinists had to offer. So – and again I’m simplifying massively – things eventually went back to a stalemate centred upon the once meaningless, and now very meaningful, 38th parallel. Warfare dragged on for another couple of years, mostly around that parallel.

And that’s how I come to the title of this piece. Operation Pressure Pump, which commenced in July 1952, came about as a result of American frustration with the stalemate. Here’s how Seth describes it:

Thousands of bombing raids destroyed every possible military and industrial target, the dams and dikes that irrigated the rice fields. Pyongyang and other northern cities began to look like Hiroshima and Nagasaki after the A-bomb, with only a few buildings standing. More bombs were dropped by the Americans on this little country of hardly more than 8 million than the allies had dropped on either Germany or the Japanese Empire in WWII. As a result, the North Koreans were forced to move underground. The entire country became a bunker state, with industries, offices and even living quarters moved to hundreds of miles of tunnels. Nonetheless, civilian casualties in these bombing raids were appallingly high.

A brief history of Korea: isolation, war, despotism and revival – the fascinating story of a resilient but divided people, p 126

Now, this was new knowledge to me, and I haven’t heard too many Americans talking about it, in the various media outlets I’ve been listening to lately, as a black mark against the country’s name – and some Americans are self-critical in this way. Okay, it was sixty-odd years ago, and since then there’s been Vietnam, Afghanistan and Iraq (twice), and a few other ‘minor’ interventions, so, who’s remembering?

So, I’ve been quite critical of the USA on this blog, and I do actually worry from time to time that I’m being unfairly anti-American. I try to relieve this concern by noting that the USA simply follows the pattern of every other militarily and economically powerful country in history. It bullies its neighbours and exploits all other regions, including its allies, to enhance its power. It also falls victim to the same fallacy that every previous powerful nation falls victim to – that its economic power is evidence of moral superiority. Their myth of American exceptionalism is arguably no worse than that of British benevolent imperialism or the civilising influence of the Roman/Egyptian/Babylonian empire. In fact, all nations are 100% self-interested in their own way. A middling country like Australia bullies smaller countries, such as East Timor over oil in the Timor Sea, while kowtowing to more powerful countries like China and the USA, in which case its self-interest lies in how to kowtow to one country without offending the other.

But let me return to Operation Pressure Pump. The greatest casualties of war are ordinary people. It’s worth dwelling on this as ordinary people currently face the consequences of stupid decisions over Iran. ‘Ordinary people’ might seem a condescending term, but it’s always worth remembering that the vast majority of people – in Iran, North Korea, Australia, the USA or elsewhere – aren’t intellectuals or politicians or national decision-makers or religious leaders or general movers and shakers – they’re people whose lives revolve around friends and family and trying to make a reasonable living. Warfare, and the damage and displacement it causes, isn’t something they can ever seriously factor into their plans. It just happens to them, a bit like cancer.

So the US bombing campaign was something that happened to the North Korean people in the early fifties. Another thing that happened to them was ‘communism’ or the despotic nationalist madness of Kim Il Sung. So they were doubly unlucky. As a humanist, I like to think my politics are simple. I consider bullies to be the worst form of human life, and I expect governments to be most concerned about protecting the bullied against the bullies, the exploited against the exploiters. I actually expect government to be an elite institution, like the media, the judiciary, and the science and technology sector. I also expect governments to put humanism above nationalism, but that’s a big ask. The UN hasn’t so far proved to be an enormous success, as members have generally put national interests above broader global interests, but it’s certainly better than nothing, and some parts of it, such the WHO and the UNHCR, have proved their value. I don’t think there’s any other option but to struggle to give more teeth to the UN, the International Criminal Court and other international oversight agencies. We should never allow one nation to accord to itself the role of global police officer. Of course these international bureaucracies are cumbersome when flashpoints occur – the aim is always to prevent these things from happening. The current Iran situation was entirely preventible, and was entirely due to the USA’s appalling Presidential system, which has allowed an irresponsible, attention-seeking buffoon to hold a position with way too much power and way too little accountability. There’s no doubt that Soleimani was an unpleasant character, but reports were that his activities were much reduced due to the Iran Nuclear Deal of 2015, a famously well-crafted deal by most accounts, which was destroyed by the buffoon.

So, this piece of unilateral bad acting by the USA takes us back to the terror bombing of North Korea in the early fifties. I’m certainly not saying that this cruelty made North Korea what it is today, but it didn’t help. We just have to learn to be more collaborative, more willing to negotiate and to understand, to hear, the other side, and stop being such belligerent male arseholes. We have a long way to go.

women and warfare, part 2: humans, bonobos, coalitions and care

Shortly before I started writing the first part of this article, I read a sad and disturbing piece in a recent New Scientist, about an Iron Age citadel in modern Iran, called Hasanlu. Its tragic fate reminded me of the smaller scale tragedies that Goodall and others recount in chimpanzee societies, in which one group can systematically slaughter another.

Hasanlu was brutally attacked and destroyed at the end of the ninth century BCE, and amazingly, the massacred people at the site remained untouched until uncovered by archeologists only a few decades ago. One archeologist, Mary Voigt, who worked the site in 1970, has described her reaction:

I come from a long line line of undertakers. Dead people are not scary to me. But when I dug that site I had screaming nightmares.

Voigt’s first discovery was of a small child ‘just lying on the pavement’, with a spear point and an empty quiver lying nearby. In her words:

The unusual thing about the site is all this action is going on and you can read it directly: somebody runs across the courtyard, kills the little kid, dumps their quiver because it’s out of ammunition. If you keep going, there are arrow points embedded in the wall.

Voigt soon found more bodies, all women, on the collapsed roof of a stable:

They were in an elite part of the city yet none of them had any jewellery. Maybe they had been stripped or maybe they were servants. Who knows? But they were certainly herded back there and systematically killed. Its very vivid. Too vivid.

Subsequent studies found that they died from cranial trauma, their skulls smashed by a blunt instrument. And research found many other atrocities at the site. Headless or handless skeletons, skeletons grasping abdomens or necks, a child’s skull with a blade sticking out of it. All providing proof of a frenzy of violence against the inhabitants. There is still much uncertainty as to the perpetrators, but for our purposes, it’s the old story; one group or clan, perhaps cruelly powerful in the past, being ‘over-killed’, in an attempt at obliteration, by a newly powerful, equally cruel group or clan.

Interestingly, while writing this on January 4 2019, I also read about another massacre, exactly ten years ago, on January 4-5 2009. The densely populated district of Zeitoun in Gaza City was attacked by Israeli forces and 48 people, mostly members of the same family, and mostly women, children and the elderly, were killed, and a number of homes were razed to the ground. This was part of the 2008-9 ‘Gaza War’, known by the Arab population as the Gaza Massacre, and by the Israelis as Operation Cast Lead. The whole conflict resulted in approximately 1200-1400 Palestinian deaths. Thirteen Israelis died, four by friendly fire. And of course I could pick out dozens of other pieces of sickening brutality going on in various benighted parts of the world today.

Attempts by one group of people to obliterate another, whether through careful planning or the frenzy of the moment, have been a part of human history, and they’re ongoing. They are traceable as far back, at least, as the ancestry we share with chimpanzees.

But we’re not chimps, or bonobos. A fascinating documentary about those apes has highlighted many similarities between them and us, some not noted before, but also some essential differences. They can hunt with spears, they can use water as a tool, they can copy humans, and collaborate with them, to solve problems. Yet they’re generally much more impulsive creatures than humans – they easily forget what they’ve learned, and they don’t pass on information or knowledge to each other in any systematic way. Some chimp or bonobo communities learn some tricks while others learn other completely different tricks – and not all members of the community learn them. Humans learn from each other instinctively and largely ‘uncomprehendingly’, as in the learning of language. They just do it, and everyone does it, barring genetic defects or other disabilities.

So it’s possible, just maybe, that we can learn from bonobos, and kick the bad habits we share with chimps, despite the long ancestry of our brutality.

Frans De Waal is probably the most high-profile and respected bonobo researcher. Here’s some of what he has to say:

The species is best characterized as female-centered and egalitarian and as one that substitutes sex for aggression. Whereas in most other species sexual behavior is a fairly distinct category, in the bonobo it is part and parcel of social relations–and not just between males and females. Bonobos engage in sex in virtually every partner combination (although such contact among close family members may be suppressed). And sexual interactions occur more often among bonobos than among other primates. Despite the frequency of sex, the bonobos rate of reproduction in the wild is about the same as that of the chimpanzee. A female gives birth to a single infant at intervals of between five and six years. So bonobos share at least one very important characteristic with our own species, namely, a partial separation between sex and reproduction.

Bonobo sex and society, Scientific American, 2006.

Now, I’m a bit reluctant to emphasise sex too much here (though I’m all for it myself), but there appears to be a direct relationship in bonobo society between sexual behaviour and many positives, including one-on-one bonding, coalitions and care and concern for more or less all members of the group. My reluctance is probably due to the fact that sexual repression is far more common in human societies worldwide than sexual permissiveness, or promiscuity – terms that are generally used pejoratively. And maybe I still have a hankering for a Freudian theory I learned about in my youth – that sexual sublimation is the basis of human creativity. You can’t paint too many masterpieces or come up with too many brilliant scientific theories when you’re constantly bonking or mutually masturbating. Having said that, we’re currently living in societies where the arts and sciences are flourishing like never before, while a large chunk of our internet time (though far from the 70% occasionally claimed) is spent watching porn. Maybe some people can walk, or rather wank, and chew over a few ideas at the same (and for some it amounts to the same thing).

So what I do want to emphasise is ‘female-centredness’ (rather than ‘matriarchy’ which is too narrow a term). I do think that a more female-centred society would be more sensual – women are more touchy-feely. I often see my female students walking arm in arm in their friendship, which rarely happens with the males, no matter their country of origin (I teach international students). Women are highly represented in the caring professions – though the fact that we no longer think of the ‘default’ nurse as female is a positive – and they tend to come together well for the best purposes, as for example the Women Wage Peace movement which brings Israeli and Palestinian women together in a more or less apolitical push to promote greater accord in their brutalised region.

Women’s tendency to ‘get along’ and work in teams needs to be harnessed and empowered. There are, of course, obstructionist elements to be overcome – in particular some of the major religions, such as Catholic Christianity, Islam, Hinduism and Buddhism, all of which date back centuries or millennia and tend to congeal or ‘eternalise’ the patriarchal social mores and power structures of those distant times. However, there’s no doubt that Christianity, as the most western religion, is in permanent decline, and other religions will continue to feel the heat of our spectacular scientific developments – including our better understanding of other species and their evolved and unwritten moral codes.

The major religions tend to take male supremacy for granted as the natural order of things, but Melvin Konner, in his book Women after all, has summarised an impressive array of bird and mammal species which turn the tables on our assumptions about male hunters and female nurturers. Jacanas, hyenas, cassowaries, montane voles, El Abra pygmy swordtails (a species of fish) and rats, these are just a few of the creatures that clearly defy patriarchal stereotypes. In many fish and bird species, the females physically outweigh the males, and there’s no sense that, in the overwhelming majority of bird species – whose recently-discovered smarts I’ve written about and will continue to write about – one gender bosses the other.

Turning back to human societies, there are essentially three types of relations for continuing the species – monogamy, polyandry and polygyny. One might think that polyandry – where women can have a harem of males to bed with – would be the optimum arrangement for a female-centred society, but in fact all three arrangements can be turned to (or against) the advantage of females. Unsurprisingly, polygyny (polyandry’s opposite) is more commonly practiced in human society, both historically and at present, but in such societies, women often have a ‘career open to talents’, where they and their offspring may have high status due to their manipulative (in the best sense of the word) smarts. In any case, what I envisage for the future is a fluidity of relations, in which children are cared for by males and females regardless of parentage. This brings me back to bonobos, who develop female coalitions to keep the larger males in line. Males are uncertain of who their offspring is in a polyamorous community, but unlike in a chimp community, they can’t get away with infanticide, because the females are in control in a variety of ways. In fact, evolution has worked its magic in bonobo society in such a way that the males are more concerned to nurture offspring than to attack them. And it’s notable that, in modern human societies, this has also become the trend. The ‘feminine’ side of males is increasingly extolled, and the deference shown to females is increasing, despite the occasional throwback like Trump-Putin. It will take a long time, even in ‘advanced’ western societies, but I think the trend is clear. We will, or should, become more like bonobos, because we need to. We don’t need to use sex necessarily, because we have something that bonobos lack – language. And women are very good at language, at least so has been my experience. Talk is a valuable tool against aggression and dysfunction; think of the talking cure, peace talks, being talked down from somewhere or talked out of something. Talk is often beyond cheap, it can be priceless in its benefits. We need to empower the voices of women more and more.

This not a ‘fatalism lite’ argument; there’s nothing natural or evolutionarily binding about this trend. We have to make it happen. This includes, perhaps first off, fighting against the argument that patriarchy is in some sense a better, or more natural system. That involves examining the evidence. Konner has done a great job of attempting to summarise evidence from human societies around the world and throughout history – in a sense carrying on from Aristotle thousands of years ago when he tried to gather together the constitutions of the Greek city-states, to see which might be most effective, and so to better shape the Athenian constitution. A small-scale, synchronic plan by our standards, but by the standards of the time a breath-taking step forward in the attempt not just to understand his world, but to improve it.

References

Melvin Konner, Women after all, 2015

New Scientist, ‘The horror of Hasanlu’ September 15 2018

Max Blumenthal, Goliath, 2013

the Vietnam War – liberation, ideology, patriotism

a heartfelt cliché from the land of the free

I’ve been watching the Burns and Novick documentary on the Vietnam War, having just viewed episode 6 of the 10-part series and of course it’s very powerful, you feel stunned, crushed, angry, ashamed, disgusted. There are few positive feelings. I have in the past called the ‘Great War’ of 1914-18 the Stupid War, from which we surely learned much, but this was yet another war whose only value was what we learned from it about how to avoid war. That seems to be the only real value of war, from which such unimaginable suffering comes. People speak of ‘collateral damage’ in war, but often, at the end of it, as in the Thirty Years’ War, the Great War, and I would argue the Vietnam War, collateral damage is all there is.

Over the years I’ve taught English to many Vietnamese people. Years ago I taught in a Vietnamese Community Centre, and my students were all middle-aged and elderly. They would no doubt have had many war stories to tell. In more recent times I’ve taught Vietnamese teenagers wearing brand labels and exchanging Facebook pics of their restaurant and nightclub adventures. For them the war is two generations away, or more. Further away in fact than WW2 was from me when I was a teenager. Time heals, as people die off.

Of course Burns and Novick provide many perspectives as they move through the years, as well as highlighting historical events and characters I knew little about, such as the Tet Offensive, the South Vietnames leaders Thieu and Ky, and North Vietnam’s Le Duan and his side-lining of Ho Chi Minh. But it’s the perspectives of those on the battlefields, wittingly or unwittingly, that hit home most.

When I was young, Vietnam was a major issue for Australians. My older brother was suspended from high school for participating in a Vietnam moratorium march in 1970. I was fourteen at the time and had no idea what ‘moratorium’ meant, except that the marchers were protesting the war. I also knew that my brother, three years older, was in danger of being conscripted and that I might face the same danger one day, which naturally brought up the Country Joe McDonald question ‘what are we fighting for’? Why were Australians fighting Vietnamese people in their own country, killing and being killed there? The unconvincing answer from government was that we were fighting communism, and that we were there to support our allies, the USA. This raises further obvious questions, such as that, even if communism was odious, it was even more odious, surely, to go to faraway countries and kill their inhabitants for believing in it. The Vietnamese, whatever their beliefs about government, were surely not a threat to the USA – that was, to me, the obvious response to all this, even as an adolescent.

Of course, the situation was more complex than this, I came to realise, but it didn’t really change the principles involved. At about this time, 1970, I happened to stumble upon a Reader’s Digest in the house, from around ’67. It featured an article whose title I still vividly recall – ‘Why not call China’s bluff in Asia?’ Written by a retired US general, it argued that the enemy wasn’t Vietnam so much as China, the root of all communist evil. China was acting with impunity due to American weakness. The USA would never win in Vietnam unless it struck at the heart of the problem – China’s support and enabling of communism throughout Asia and elsewhere. The general’s answer was to show them who had the real power – by striking several major Chinese cities with nuclear bombs.

Killing people was wrong, so I’d heard, but apparently communism was even more wrong, so the ethics were on this general’s side. Of course I was disgusted – viscerally so. These were apparently the kind of people who ran the military. Then again, if people are trained to kill, it’s tough not to allow them the opportunity… and they’re only Chinese after all.

I must make an admission here. I don’t have a nationalistic cell in my body. I’ve just never felt it, not even slightly. Okay, sure I support Australia in soccer and other sports, just as I support local teams against interstaters, insomuch as I follow sport. But I’ve never in my life waved a flag or sung a national anthem. When I first heard the Song of Australia being sung at school assembly, as the national flag was hoisted, I noted that the words extolled the wonders of Australia, and presumed that other anthems extolled the virtues of Guatemala, or Lesotho, or Finland, and I could have been born in any of those countries or any other. It all seemed a bit naff to me. Maybe the fact that I was born elsewhere – in Scotland – made me less likely to embrace the new country, but then ‘God Save the Queen’ – could anything be more naff than that little ditty?

So the idea of my possibly being forced to fight in a foreign war just because I’d landed up in a country whose rather vague ANZUS obligations supposedly entailed an Australian presence there seemed bizarre. I couldn’t look at it from a nationalist perspective (had I known the term at the time I would’ve called myself a humanist), which freed me up to look at it from a more broadly ethical one. From what I gathered and am still gathering, the US intervention in Vietnam, which began with Eisenhower and even before, with US military assistance to French colonial rule in Indo-China, was fueled first by the essentially racist assumption that South-East Asians weren’t sufficiently civilized to govern their own regions, and then by the ‘better dead than red’ ideology that caused so much internal dissension in the US in the fifties. The idea, still bruited today, that the ‘rise of communism’ was a direct threat to the USA seemed far-fetched even then. The Vietnamese, it seemed obvious, had been fighting off the French because, as foreigners, they had little interest in the locals and were bent on exploitation. Naturally, they would have looked at the Americans in the same way. I certainly had little faith in communism at a time when Mao and the Russian leadership seemed to be vying for ‘most repressive and brutal dictator’ awards, but I didn’t see that as a threat to the west, and I also had some faith that a fundamentally unnatural political system, based on a clearly spurious ideology, would die of its internal contradictions – as has been seen by the collapse of the USSR and the transformation of China into a capitalist oligarchy.

So it seemed to me at the time that the Vietnamese, whatever their political views, aspirations and allegiances, were above all bent on fighting off foreigners. They were seeking autonomy. The problem was that foreigners – the Americans and their allies, as well as the Chinese and the Soviets – were all seeking to influence that autonomy to their own national and ideological benefit. Of course, the Vietnamese themselves were ideologically divided (as is every single nation-state on this planet), but the foreign actors, and their military hardware, gave those divisions a deadly force, leading to Vietnamese people killing Vietnamese people in massive numbers, aided and abetted by their foreign supporters.

War, of course, brutalises people, and some more than others. That’s where the nationalism-humanism divide is most important. That’s why, in watching the Vietnam War series, I’m most moved by those moments when patriotic bombast is set aside and respect and admiration for the courage and resolution of the Vietnamese enemy is expressed. It’s a respect, in the field, that’s never echoed, even in private, by the American leaders back in Washington. So often, patriotic fervour gets in the way of clear thinking. I was watching the last moments of the sixth episode of the series, when Hal Kushner, a doctor and POW in Vietnam, was speaking in a heartfelt way of his experience there: ‘we understood that despite different backgrounds’, he said, ‘different socioeconomic backgrounds, different races, different religions, that we were… Americans.’ I actually thought, before he uttered that last word, that he was going to make a statement about humanism, the humanity of all parties, at last saying something in stark contrast to his patriotic pronouncements up to that point. But no, he wasn’t about to include the Vietnamese, the enemy. Of course, Kushner had had a bad time in Vietnam, to say the least. He’d been captured and tortured, he’d seen many of his comrades killed… I could certainly understand his attitude to the Vietnamese who did these things, but I could also understand the rage of the Vietnamese, equally patriotic no doubt, when they saw this horde of fucking foreigners coming over with their massive weaponry and arrogance and fucking up their country, destroying their land for years, bombing the fuck out of village after village without discrimination, killing countless babies and kids and young and old folk, male and female, all to prevent the Vietnamese from installing a government of their own choosing just in case it wasn’t sufficiently in keeping with the will of the US government. If patriotism blinds you to this unutterable inhumanity, than it’s clearly a sick patriotism.

I look forward to watching the rest of the series. I wonder who’ll win.

solving the world’s problems, one bastard at a time..

Canto: Let’s talk about something more gripping for a while. Like, for example, the global political situation.

Jacinta: Mmmm, could you narrow that down a bit?

Canto: No, not really… Okay, let’s take the most politically gripping issue of the moment, the possibility of nuclear annihilation for thousands of South Koreans or Japanese – and then North Koreans – due to the somewhat irresponsible launchings and detonations of massively destructive weaponry by a guy who we can reasonably assume to be intoxicated with his own power – and I do believe power to be the most toxic and dangerous drug ever conceived. And then we can talk about all the other issues.

Jacinta: Well as for the Kim jong-un issue, I suspect I can speak for a lot of people when I say I oscillate between dwelling on it and dismissing it as something I can do nothing about. What else do you want me to say. To say I’m glad we’re not in the way of it all would seem inhumane…

Canto: Do you have any solutions? What should we do from here?

Jacinta: We? You mean ‘the west’? Okay, from here on in, I’d cease all direct communications with Kim – all threats, all comments, everything. That only seems to make him worse.

Canto: But it can hardly get worse. Don’t we need to act to remove his threats, which are a bit more than threats?

Jacinta: Well of course the best solution, out of a bad lot, would be to have him disappear, like magic. Just deleted. It’s impossible, but then I’ve heard some people do six impossible things before breakfast.

Canto: He’s only 33 apparently, and according to Wikipedia he’s married but childless…

Jacinta: I’m not saying deleting him would be a good option, it’d presumably cause chaos, a big power struggle, a probable military takeover, unpredictable action from China, and all the weaponry, such as it is, would still be there. And we have no idea how to do it anyway.

Canto: I’m sure they have some plan of that type. The CIA’s not dead yet.

Jacinta: Yeah I’m sure they have some back-drawer plan somewhere too, but I wouldn’t misunderestimate the incompetence of the CIA.

Canto: So what if we follow your do-and-say-nothing policy? Don’t aggravate the wounded bear. But maybe the bear isn’t wounded at all. NK just detonated something mighty powerful, though there’s some controversy over whether it was actually thermonuclear. Anyway it’s unlikely the country just developed this powerful weapon in the few months that Trump has been acting all faux-macho. Who knows, this may have taken place if Clinton or someone else was in power in the US.

Jacinta: Interesting point, but then why are so many people talking about tit-for-tat and brinkmanship? They may have had the weapon, and maybe a lot more, but Kim’s decision to detonate it now, to show it, seems to have been provoked. It’s classic male display before a rival. Think of the little mutt snapping at the mastiff’s heels. Fuck you, big boy, I’ve got teeth too.

Canto: Yeah, but this little mutt has teeth that can wipe out cities. In any case, now he’s been provoked, and it’s unlikely that Trump and his cronies are going to damp down the belligerent rhetoric, the rest of us seem to be just sitting tight and waiting for this mutt to do some damage inadvertently/on purpose, and then what will happen? Say a missile goes astray and lands on or near a Japanese city? Untold casualties…

Jacinta: I think China will be key here. Not that I have any faith in the Chinese thugocracy to act in any interest other than its own.

Canto: Or the Trumpocracy for that matter.

Jacinta: I suspect China might step in and do something if it came to the kind of disaster you’ve mentioned. Though whether they have a plan I don’t know. I wouldn’t be surprised, actually if they’re having urgent closed-door talks right now on how best to take advantage of the crisis.

Canto: Well don’t worry, Trump and our illustrious leader are have a phone call today to sort it all out.

Jacinta: I’m really not sure what there is to talk about. An American first strike would have horrific cascading effects, and upping the tempo of military exercises in the neighbouring regions will just make Kim more reckless, to go by past experience. So if we don’t have any communication directed at him, he might continue with building bombs, but he would’ve done that anyway. So, though we’re not making matters any better, neither are we making them worse, which we are doing by goading him. Meanwhile we should be talking around NK. It’s like the elephant in the room. No sense talking to the elephant, he doesn’t speak our language (actually that’s a bad example, as intelligent mammals elephants have a lot in common with us…). Anyway we should be talking to significant others to try to build a team that can deal with the elephant.

Canto: Teamwork, that seems highly likely.

Jacinta: Yeah, I know everyone has a different agenda with regard to the elephant, but surely nobody wants to see anyone nuked. And the US shouldn’t be wasting its time talking to Australia, though I suspect Trump will be talking to Turnbull re troop commitments rather than any serious solution.

Canto: And by the way, we’re talking about Trump here, he’s never going to quit with the macho bluster. That’s a given.

Jacinta: All right so all we can do is hope – it’s out of our hands. But it seems to me that all his advisers are telling him a first strike isn’t an option, so maybe he will listen.

Canto: Maybe he’ll listen about the first strike, but he won’t stop the bluster and the goading. So Kim will continue to react by testing missiles and such, until something goes horribly wrong, and Trump will feel justified in delivering a second strike, and things’ll get very bloody and messy.

Jacinta: Okay, you’re getting me depressed, but if I can return to teamwork, the thing to do is get the team on board – the UN as well as the key players, China, Russia and of course South Korea and Japan. That means putting aside all the bad blood and really working as a team.

Canto: To do what? Get NK to stop producing nukes? Putin has already said that would be a no-goer, given their position.

Jacinta: Right, so that would be a starting point for discussion. Why does Putin think that, and what would be his solution, or his advice? And China’s? I’m assuming everybody’s uncomfortable about NK, though some are clearly more uncomfortable than others. So get a discussion going. What does Russia think the US should do about NK? What does China think Russia should do? Does anyone have good advice for South Korea?

Canto: You’re being hopelessly naive. I suspect Russia and China would approach this issue with complete cynicism.

Jacinta: Well let’s be well-meaning rather than naive. I think we’re inclined to be a co-operative species. I think cynicism can dissipate when confronted with a genuine desire to listen and co-operate. You know I’ve described all of the main actors here – Trump, Putin, Li Keqiang and his henchmen, and of course Kim Jong-un, as macho scumbags and the like, but maybe its time to appeal to the better angels of their natures, and ours, to find a peaceful resolution to this mess.

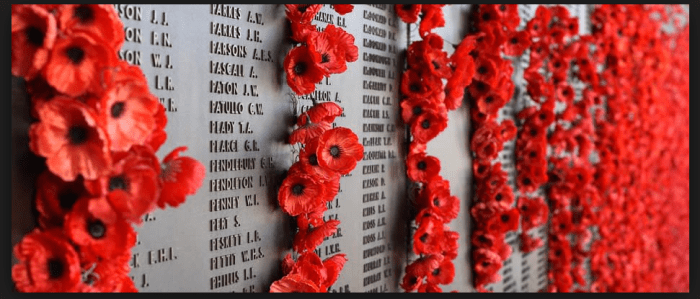

nationalism, memes and the ANZAC legend

Canto: Okay, I get livid when I hear the unquestioning and unquestioned pap spoken about the Anzacs, year in year out, and when I hear primary teachers talking about their passion for Anzac Day, and teaching it to impressionable young children. Not sure how they will teach it, but when such remarks are followed by a middle-aged woman knitting poppy rosettes and saying ‘after all, if it wasn’t for them [the Anzacs] we would’t be here’, I’m filled with rage and despair about the distortions of history to suit some kind of nationalist pride and sentimentality.

Jacinta: Yes, that sort of thing leads to innocent, impressionable young children parroting the meme ‘they died so we could be free’.

Canto: Or in this case the even more absurd ‘they died so that we could exist’…

Jacinta: On the other hand, to be fair, many young people go off to Anzac Cove to commemorate their actual grand-fathers or great-great uncles who died there, and they’re captivated by their story of sacrifice.

Canto: Yes, and this memory should be kept, but for the right, evidence-based reasons. What did these young men sacrifice themselves for, really?

Jacinta: Well as we know, the reasons for the so-called Great War were mightily complex, but we can fairly quickly rule out that there was ever a threat to Australia’s freedom or existence. Of course it’s hard to imagine what would have happened if the Central Powers had won.

Canto: Well it’s hard to imagine them actually winning, but say this led to an invasion of Britain. Impossible to imagine this lasting for long, what with the growing involvement of the US. Of course the US wasn’t then the power it later became, but there’s little chance it would’ve fallen to the Central Powers, and it was growing stronger all the time, and as the natural ally of its fellow English-speaking nation, it would’ve made life tough for Britain’s occupiers, until some solution or treaty came about. Whatever happened, Australia would surely not have been in the frame.

Jacinta: Britain’s empire might’ve been weakened more quickly than it eventually was due to the anti-colonisation movement of the twentieth century. And of course another consequence of the Central Powers’ victory, however partial, might’ve been the failure or non-existence of Nazism…

Canto: Yes, though with the popularity of eugenics in the early twentieth century, master-race ideology, so endemic in Japan, would still have killed off masses of people.

Jacinta: In any case your point still holds true. Those young men sacrificed themselves for the British Empire, in its battle against a wannabe Germanic Empire, in a war largely confined to Europe.

Canto: But really in order to understand the mind-set of the young men who went to war in those days, you have to look more to social history. There was a naive enthusiasm for the adventure of war in those days, with western nations being generally much more patriarchal, with all the negative qualities entailed in that woeful term.

Jacinta: True, and that War That Didn’t End All Wars should, I agree, be best remembered as marking the beginning of the end of that war-delighting patriarchy that, in that instance, saw the needless death of millions, soldiers who went happily adventuring without fully realising that the massive industrialisation of the previous decades would make mincemeat out of so many of them. I’ve just been reading and watching videos of that war so as not to make an idiot of myself, and what I’ve found is a bunch of nations or soi-disant empires battling to maintain or regain or establish their machismo credentials in the year 1914. With no side willing to give quarter, and no independent mechanisms of negotiation, it all quickly degenerated into an abysmal conflict that no particular party could be blamed for causing or not preventing.

Canto: And some six million men were just waiting to get stuck in, an unprecedented situation. And what happened next was also unprecedented, a level of carnage never seen before in human history. The Battle of the Frontiers, as it was called, saw well over half a million casualties, within a month of the outbreak.

Jacinta: And so it went, carnage upon carnage, with the Gallipoli campaign – unbearable heat, flies, sickness and failure – being just one disaster among many. Of course it infamously settled into a war of attrition for some time, and how jolly it must’ve been for the allies to hear that they would inevitably be the victors, since the Central Powers would run out of cannon fodder first. It was all in the maths. War is fucked, and that particular war is massively illustrative of that fact. So stop, all teachers who want to tell the story of the heroic Anzacs to our impressionable children. I’m not saying they weren’t brave and heroic. I’m not saying they didn’t do their best under the most horrendous conditions. I’m certainly not saying their experience in fighting for the mother country was without value. They lived their time, within the confines and ideology of their time, as we all do. They played their part fully, in terms of what was expected of them in that time. They did their best. And it’s probably fair to say their commanders, and those above them, the major war strategists, also did their best, which no doubt in some cases was better than others. Even so, with all that, we have to be honest and clear-sighted and say they didn’t die, or have their lives forever damaged, so that we could be free. That’s sheer nonsense. They died so that a British Empire could maintain its ascendency, for a time, over a German one.

Canto: Or in the case of the French and the Russians, who suffered humungous casualties, they died due to the treaty entanglements of the time, and their overlords’ obvious concerns about the rise of Germany.

Jacinta: So all this pathos about the Anzacs really needs to be tweaked, just a wee bit. I don’t want to say they died in vain, but the fact is, they were there, at Gallipoli, in those rotten stinking conditions, in harm’s way, because of decisions made above their heads. That wasn’t their fault, and I’m reluctant, too, to blame the commanders, who also lived true to their times. Perhaps we should just be commemorating the fact that we no longer live in those macho, authoritarian times, and that we need to always find a better way forward than warfare.